State touts diversity report, but most specialty cannabis businesses not yet open

Illinois' cannabis market is booming and the state is diversifying new licenses, but significant hurdles remain for companies wanting to enter the expanding market, according to an independent industry study.

The celebratory news release cited several industry successes in recent months, including the opening of the state's 100th socially equitable cannabis dispensary and cannabis sales expected to surpass $1 billion in 2024.

Gov. JB Pritzker has repeatedly said social equity is at the core of Illinois' cannabis program since signing the Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act in 2019. In July, the governor praised a newly commissioned independent diversity report on the industry that identified progress and challenges toward established diversity goals.

An independent diversity study the state commissioned from Peoria-based consulting firm Nerev Group at a cost of $2.5 million found that while Illinois has awarded more licenses to women and people of color than any other regulated market in the U.S., white men remain the demographic most likely to obtain a cannabis license in Illinois.

But only about 30% of businesses that receive cannabis-only licenses are actually operating, according to the USDA's most recent licensee business status list, and some social equity applicants have had difficulty turning their licenses into operating businesses.

Many of the law's lofty goals have been slow to materialize for social equity employers — those who live in areas historically affected by the drug war or have been personally affected by it: Of the roughly 50 dispensaries opened by social equity employers by last summer, only 15 were owned by people of color, according to IDFPR's annual report on cannabis last year.

State data shows that while minority- and women-owned businesses hold most of the lower- and specialty-level licenses, more than three-quarters of cultivation licenses are held by white, male-owned businesses that have dominated the industry since marijuana was legalized for medical use.

Funding Barriers

The first cannabis dispensaries licensed through the state's Social Equity Lottery program wouldn't open until late 2022, nearly a decade after the first cannabis plants and businesses took hold in Illinois since the state was legalized for medical purposes in 2013.

As part of the 2019 legalization law, lawmakers created a category of “craft cultivation” licenses aimed at giving Illinoisans who wanted to grow and sell marijuana legally more opportunities. But existing cultivation centers — often owned by large, publicly traded companies — that had been growing cannabis for the state's medical program since 2014 were only approved to grow cannabis for adult-use dispensaries in late 2019.

A report commissioned by the state's Office of Cannabis Regulation and Oversight highlighted a number of challenges facing craft grow operations. First, marijuana remains illegal under federal law, making banks and lenders hesitant to invest in the industry.

After a highly detailed application process that took about three months to complete, Reese Xavier was awarded a craft cultivation license through the state's Social Equity Lottery in 2021. Three years later, he still doesn't have enough capital to build a brick-and-mortar store to grow his cannabis plants, despite receiving a loan from the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

Xavier said he's still “fully committed” but is having difficulty finding the capital needed to begin construction — perhaps the most common and prominent hurdle small cannabis businesses face, as opening a cultivation center or dispensary can cost millions of dollars.

“The common misconception, and I now know that's a misconception, was that you don't have to worry about money – 'Once you win the license, the money will come to you.' But that's absolutely not true. Access to capital is the biggest challenge,” he told Capitol News Illinois.

Last year, through DCEO’s Social Equity Loan Program, the state provided nearly $20 million in forgivable loans to a total of 33 licensed craft growers, injectors and transporters. Nearly all of the transporters that were awarded loans are still in business, but more than a year later, only 40% of the craft growers and injectors that received loans have resumed operations.

Last month, DCEO announced more than $5 million in loans to 17 companies that own more than 20 dispensaries in the state, most of which already sell to adults.

Erin Johnson, the state's top cannabis regulator, told Capitol News Illinois that state officials had to overcome federal hurdles, but more loans will be available to professional licensees later this year.

“Given the fact that cannabis is still illegal under federal law, funding is a major challenge for the agency,” she said. “We will open applications by the end of this year to provide an additional $40 million in direct forgiveness loans for all license types.”

The advantages of large companies

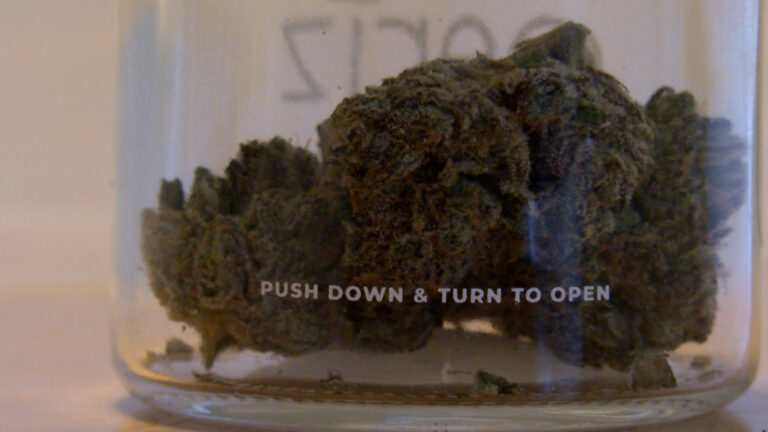

Xavier holds licenses to grow marijuana and turn it into products such as vaporizer oils and tinctures, which it then sells wholesale to dispensaries, which can then retail the products to customers.

Specialty marijuana businesses — a category added to state law when lawmakers legalized recreational cannabis — can obtain licenses to cultivate, infuse and transport marijuana products, meaning these businesses have fewer avenues to make profits compared to companies that own comprehensive cultivation centers.

This diagram shows the journey of Illinois-grown cannabis from manufacturer to consumer. Illustration by Dilpreet Raju for Capitol News Illinois

In Illinois, about 20 large operators — including Shelby County Community Services, a Shelbyville nonprofit — are licensed to operate cultivation centers where they grow, cure, package and sell marijuana flower and other products such as edibles to dispensaries.

One challenge for craft growers is that they are limited to 5,000 square feet of canopy space to grow cannabis flower, which the report said “does not generate sufficient profits necessary to secure financial support.” The 5,000-square-foot canopy requirement also “limits their ability to produce enough cannabis to build brand loyalty across Illinois markets,” the report said.

The Cannabis Regulation and Tax Act allows the USDA to increase craft growers' canopy space in 3,000-foot increments up to a maximum of 14,000 square feet.

Cultivation centers, on the other hand, have spaces up to 210,000 square feet (roughly the size of a city block) where cannabis can be grown, and some have multiple cultivation centers, allowing them to produce 15 to 120 times more cannabis than individual craft growers.

The state-commissioned report found that these restrictions on craft growers have led to slower economic growth for craft license holders.

Of the 87 licenses awarded to craft cultivation operations, only 21 have been approved to build, and of those, 16 are open, according to the Department of Agriculture. HT 23, Xavier's craft cultivation cannabis operation, is one of five operations approved to build but not yet open.

A state-commissioned report found the craft growing operation's compound for the injectors was defective.

“Cannabis infusers need a product called cannabis distillate, which is sourced exclusively from commercial growers,” the report states. “While it is technically possible for craft growers to produce distillate to sell to infusers, many growers report that they are unlikely to do so due to limited growing space.”

The company identified other distillate options for its injectors as prohibitively expensive.

“Many infuser participants stated that growers were pricing distillate well above fair market value,” the report continues. “They also stated that growers were inconsistent in pricing distillate and that they had to have a pre-existing relationship with the grower to get a fair deal.”

Xavier said he would like to speak more directly with Illinois lawmakers and regulators to help them understand the challenges licensees face.

“These things seem like simple things, but what we're learning is that not everything is simple,” Xavier said, adding that he would like to see the state spend “more time and energy” listening to social equity licensed businesses.

Bills introduced during the Illinois General Assembly's spring legislative session aimed to address issues for small cannabis operations, such as requiring growers to set aside a certain amount of concentrates for injectors to purchase, but many of them stalled for lack of sufficient support.

Other criticisms

A report released in July by the National Black Empowerment Action Fund, a national advocacy group that supports black entrepreneurs, criticized Governor Pritzker for approving a legal framework that benefits large corporations while denying access to aspiring black entrepreneurs.

The report argues that too few pharmacy licenses are awarded to businesses owned by people of color.

“Pritzker was all talk and no action,” the NBEAF report said. “Instead, he allowed white owners to gobble up the most profitable parts of the market.”

Johnson, the state's cannabis regulator, said minority-owned dispensaries in the state that have opened since 2020 have increased from 20% to about 50%.

For employers that don't meet the state's social equity standards, state law considers employers to be social equity businesses if they employ at least 50 percent of their employees who meet the state's criteria for being affected by the drug war. But Johnson said he doesn't know how many businesses qualify as social equity businesses based on the makeup of their workforce, and state law allows licensees to keep that information confidential.

Social equity dispensaries accounted for less than 4% of Illinois' cannabis industry's revenue of more than $1.5 billion in fiscal year 2023, according to the NBEAF report.

The Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation's 2023 cannabis annual report states that “this number is expected to continue to grow” as more social equity dispensaries open, but NBEAF argues that licensees are taking too long to get a foothold.

Editor's note: This is part two of a two-part series on the state's marijuana industry. Read part one here.